Betrayal is a semi-cooperative asymmetric team structure where one or more players work against the objectives of their allies. Betrayal can be as simple as a player breaking a promise made to another player, or as verbose as multiple betrayers covertly working together to overthrow an alliance. However, the most common iteration of betrayal involves a single player secretly pursuing rogue goals counter to that of the alliance of which they’re a member.

The central concept of betrayal is based on the tension between multiple players openly working together but secretly trying to backstab one another. The uncertainty and mystery from asymmetric information encourages investigation of a player’s true intents, while trying to suppress other player’s efforts to do the same to you.

For example, in the social role-playing game The Resistance, players play as a resistance movement, but among them some of the players are secret spies that try to clandestinely thwart the resistance’s efforts by interrupting their missions.

The nature and style of a game can change drastically depending on several factors, such as the dynamic of the opposing teams, what information is being kept secret, how the information is exchanged, and what implications or ramifications arise if that information is revealed.

Table of Contents

Betrayal Types

Betrayal mechanics can be divided into two main categories: circumstantial betrayal and intentional betrayal.

- Circumstantial Betrayal: A game that allows (but does not mandate) players to betray one another, mostly based off changing circumstances of the game. Betrayal is always a concern anytime a player makes two conflicting promises. The classic example of two players who agree not to harm each other’s efforts, but later in time renege on their commitments due to one player becoming a larger threat to the other. Circumstantial betrayals are optional and intermittent.

- Intentional Betrayal: A game that adopts more formal teams (see static teams) and employs methods for each team to harm one another from within their own ranks. For this to work, the two teams must be interdependent in some way (e.g. some players are members of both teams). A common method used is for one of the team’s roster to be kept secret from the rest of the players.

Player Roles

In betrayal games, it’s common for players to adopt explicit roles. These roles grant players special abilities, asymmetric goals, resources, and so on that they can use to elicit information, investigate other players, alter elections, and test accusations.

- Loyalist/Regular: These are the players who are members of an alliance but are unaware of who amongst them are traitors.

- Leader: One of the loyalist players is deemed a leader, who usually knows more in-game information than the other players (such as the identity of one or more betraying players).

- Traitor/Resistance Fighter: The player who takes on an offensive role to internally betray and oppose one of their team’s goals. The primary goal is to either covertly disrupt & sabotage the alliance or cause enough intramural chaos to force their team to lose. If the betrayer’s team loses then they win the game.

- Sympathizer: In games with more than one betrayer, there may be players who take on a sympathetic (but passive) role towards the betrayer. The sympathizer provides support to the betrayer by covertly (or clandestinely) offering them resources, units, communications, or even a “backdoor” into their current team’s defenses for the betrayer to exploit. Typically the sympathizer is in a privileged or high-ranking position. An alternative is for the sympathizer to be a betrayer but who does not know who the other betrayers are.

- Assassin: A betrayer who can attempt to eliminate the leader, if they can deduce who that is.

- Bodyguard: A loyalist player who attempts to protect the leader player, if they can deduce who it is they’re supposed to be protecting.

- Spy/Informant: A betrayer that plays a supportive role for other betrayers. The spy offers aid to the traitor by engaging in espionage, surveillance, reconnaissance, or elicitation, then passing that information to the betrayer. The spy may also simply work to keep the betrayer’s secrets hidden.

- Agent Provocateur: A betrayer that attempts to persuade, influence, or even recruit players to do the bidding of the traitor’s side. The provocateur’s goal is to manipulate how other players vote, play the game, or even affect the relationships between teams. The provocateur may try to cover for a betrayer’s disruptive actions by shifting blame to a scapegoat, or using a “false flag” as a deliberate misrepresentation of someone’s affiliation or motives.

- Double Agent: A player who claims to secretly work against their own team (and on the betrayer’s side) but is actually still loyal to their alliance. The double agent’s efforts are to gather intelligence against the resistance from inside the resistance’s cabal. The double agent may also try to reveal the secret identity of the betraying players.

- Defector: A player who may switch sides at a random interval within the game. They may switch sides multiple times, depending on the rules of the game.

- Activist: A neutral player who only wins if they can persuade other players to vote or act a certain way concerning various issues. For example, the activist may only win the game if they can convince everyone else to unanimously vote to have them eliminated.

Player Abilities

Players with certain roles, abilities, or membership to specific teams, can develop ways to influence the game. The most common player ability in betrayal games is for a player to reveal (either publicly or in private) certain pieces of information (e.g. the true role of a player).

Players may also gain (either permanently or temporarily) the ability to unilaterally eliminate another player. A less-extreme variation is to instead have another player’s special abilities be suppressed or removed.

Team & Goal Structures

Though most betrayal games involve only two teams (an alliance and a resistance), multiple other teams can exist as well. For example, a tertiary team can play a neutral role between the opposing sides. In fact, not only can multiple teams exist, but multiple team structures can as well. For example, one team could be static, while another could be dynamic; or the betrayers could oppose one another in a free-for-all format, or instead work cooperatively.

Similarly, most betrayal games exhibit asymmetrical teams where the number of traitorous players are outnumbered by loyal players. However, betrayal games could have team parity or even more traitors than loyalists.

The goals of each team could be different. Team goals do not necessarily have to be mutually exclusive, but could instead opt for lateral objectives. For example, one team’s goal may be concealment while another team’s goal is elimination. A third team’s goals may be contact or even rescue.

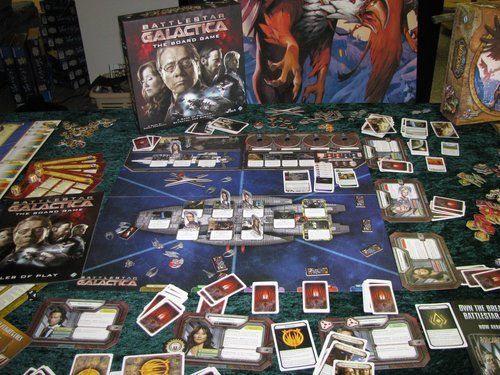

An example of this can be found in the board game Battlestar: Galactica where the players who play on the human’s team have the goal of trying to survive Cyclon attacks and reach planet Earth before they’re destroyed. In contrast, the Cylon players (who are also secret betrayers) try to help the Cylon navy destroy the Galactica spaceship.

Voting

Voting mechanisms are common in betrayal games. Players are encouraged to discuss and vote on a variety of topics; all the while knowing that one or more secret conspirators may be in their midst. It’s commonplace for a team to vote on marshaling their forces, pooling their collective resources, or simply to overcome a challenge presented by the game. Traitors can attempt to sabotage the team’s unity by casting a dissuading ballot in the blind-voting process. The votes are collected, anonymized, and tallied.

If the betrayer voted to hinder the group’s efforts, the election fails. However, not all ballots must be kept secret. For example, its natural in betrayal games for players to openly vote on who among them they believe should be eliminated (see below).

For example, the social deduction game Werewolf has players pitted against each other in roles as villagers and werewolves. Each night, werewolves can secretly plot which villager they wish to slay. However, during the day, villagers can convene and openly vote on who they believe is secretly a werewolf (and have them subsequently executed). After all the players of one side are eliminated, the other side wins the game.

Players try to interpret the outcome of an election, how individual players may have cast their vote, and why; all in an attempt to uncover a player’s true intentions.

Elimination

The possibility of players to eliminate (either democratically through vote or unilaterally) other players whom they suspect are secretly (or obviously) not on their side is a common theme in betrayal games. For betraying players, the elimination process must not be linked back to them. Similarly, player roles and allegiances may optionally be publicly revealed or even secretly swapped with other players, if the game permits.

Communication

Because players are often encouraged to accuse other players of in-game improprieties, discuss theories and facts, and reach an agreement on team actions, player communication is important.

As an example, the classic board game Mystery of the Abbey, although not technically a betrayal game, centers on player collecting clues about a murder that takes place in a religious abbey. Players then trade pieces of information, steal clues, or reveal secrets.

Communication can be formally structured, restricted, or permitted with specific stipulations. By adding such constraints, the game can then later grant these liberties, or deem them permissible only for certain player roles, allegiances, actions, resources, units, and so on.

Bluffing

Lying, misleading, and arguing convincing arguments are crucial for betrayal games. Imposter players must be able to hide and cover up their seditious acts, while normal players must try to discern fact from fabrication. Similarly, players may be permitted to make in-game posturing which carry dire implications & threats for the opposing team.

Information

The true identity of a traitor, a player’s real allegiance, and the responsible party of certain in-game events and actions are all important pieces of information. In betrayal games, its common to share, reveal, or trade this information with other players. Such information can be incriminating by itself, or divided up into many smaller clues that must first be collected and analyzed before its salacious nature is revealed.

Benefits

Betrayal creates tension by adding uncertainty, asymmetric information, surprise, and asymmetric goals. Players are encouraged to both work together but also covertly against one another.

Players tend to betray other players whom they perceive as being untrustworthy and morally distasteful. Players also may derive pleasure in correctly investigating and unmasking a traitor.

With the right game group, betrayal dynamics act as excellent fodder for memorable moments in the game. Betrayal games are perhaps best played with close friends or an extroverted group.

Consequences

Betrayal can cause friction between players. The more devastating the betrayal, or more dependent the player was on the alliance, the more friction the treachery can cause. Likewise, the very possibility of betrayal can have a negative effect on team work and communication.

Players who do not enjoy deception or backstabbing may wish to avoid betrayal games, as both actions are encouraged in betrayal games.

Players new to the game who are secretly chosen to be a betrayer may find themselves with questions regarding their abilities and game rules. However, they will feel discouraged to ask questions lest they inadvertently reveal their secret identity.